The Quantitative Model of Civil War Onset and the American Civil War

Since the end of the War of Northern Aggression, scholars have sought to understand what drove the United States into conflict with itself. Many interpretations on the causation of the conflict, center around three prevailing narratives which fail to fill in major gaps in our understanding. A remedy to the gaps in this understanding needed to be found, and so new methods of analyzing the historical record and the events that led to the onset of the war have been sought. One potential avenue that has aided in understanding the causation of the conflict, can be found in research done by economists Paul Collier and Anke Hoeffler. In their work titled Greed and Grievance in Civil War published in 1999 for the World Bank, an in-depth analysis was conducted on every case of civil war between 1960 and 1999.

This research came to some profound conclusions of which Collier and Hoeffler were able to create an analytical model that can be used as a tool to predict the outbreak of civil war in the future. Their research concluded that civil conflict in contemporary instances, was empirically linked to the predation and capture of resources. It has shown that demographic and geographic pressures on the population of a nation, are important factors in the development of civil conflict in a nation, and that the stages of national development are also key. What was most profound, is that the research showed that ethnic and religious fractionalization have little to do with the causation of civil conflict, and instead are used as justifications to continue violence. In essence, the result of this study takes an academic hatchet to the common grievance-based understandings of civil conflict. Instead of understanding conflict as an attempt to redress grievances, this paper shows definitively that envy and greed drive conflict.

Though Collier and Hoeffler looked to contemporary and future instances of civil conflict in their study, I immediately began to wonder if the model and its findings could be used in a historical context. I am not an economist, and I knew that most of the inputs that this model needs to function would be difficult or improbable to find. This caused me to look at the general findings of the research and use them as a lens to view civil conflicts of the past. I set out to do this in a paper title Blood, Money, and Cotton: Greed, Grievance, and the American Civil War, and feel confident that the use of this model greatly aided in forming a new interpretation of the causation of the war without the glaring gaps that have been found in the interpretations presented by others.

The purpose of this article is to provide a generalized summation of my research and conclusions. It will address the Quantitative Model of Civil War Onset, its findings, and the key ways that this model works to better our understanding on the causation of the American Civil War. In this work we will address how the Northern desire to plunder the resources of the South, the demographic imbalance that existed in the nation, combined with geography, fractured economic development, and the economic catastrophe that began in 1859 to create the most violent and devastating conflict in American history.

To begin with, it is important to understand the prevailing narratives that exist on the causation of the war. While there are some off shoots, the two prevailing narratives can be found in regard to our understanding of the causes of the war. These cand be viewed as the Righteous Cause and Lost Cause narratives. Both of these narratives present different and often opposing views of the conflict, but they are incomplete and leave gaps in our collective understanding of the war’s causation. This is not the only issue with the narratives however, as they are extremely biased and at times lean heavily on assumptions that the historical record suggests are not well thought out.

The Righteous Cause narrative is objectively the most guilty of relying on these assumptions. The main points of this narrative are well known to most and consist of the idea that the conflict was due to slavery and an immense desire by Northerners to preserve the Union. Authors like James Ford Rhodes, Allan Nevins, and Bruce Levine, have all used this narrative to proclaim the North to be morally justified in their cause, but when further scrutiny is applied, their position is shown to be unsound. If opposition to the institution of slavery was a prime driver of secession, then why was secession not unanimously favored among southern slaveholders? If slavery was protected by the Constitution and there was little chance that change could come about politically, then why would southern states want to secede. Just prior to the onset of the war, SCOTUS had ruled that slavery could not be banned from the territories. If that’s the case, then the southern states had no reason to believe that slavery was truly endanger, and there would have been no reason to secede to preserve the institution.

The Lost Cause narrative is a more accurate view of the conflict, but even so, this interpretation is still incomplete. This narrative focuses on states’ rights disputes and northern military aggression, while viewing the institution of slavery as a minor issue in the onset of the conflict. The problem with this narrative tends to be its unwaveringly biased southern stance and its disdain for any information presented that is contrary to this position. This narrative is also plagued by its sole reliance on ideological differences as a main driver of the conflict. With any serious amount of investigation, this view does not hold firm. If ideological differences were the main driver of secession, then how could democrats in the North justify participating in the war on the northern side? How could Constitutional Unionist justify their acceptance of secession and aid to the cause of the southern states? Since the majority of the abolitionist in the nation actually resided in the southern states, how could we say that the war was based on ideological differences centered around slavery? The reality is, that we cannot balance these claims with the reality of the time.

The Quantitative Model of Civil War Onset as developed by Paul Collier and Anke Hoeffler, works on a greed-based theory of conflict, as opposed to the traditional grievance-based theory. Collier states that while the possibility of a grievance-based conflict exists, the likelihood of such a conflict manifesting or being feasible is extremely slim. Due to the elements that are necessary for a revolutionary movement or group to form and reach feasibility, a greed-based rebellion or conflict is vastly more probable. Because his research centered around greed, Collier was able to isolate similarities between all the civil conflicts that were studied. This allowed him to create a model that can be used to show the likelihood of civil conflict in nations. Collier, however, does not discount grievances in the creation of a conflict. Instead, he views grievance as an important facet in justifying violent action.

Through this research, the authors conclude that “The incidence of rebellion is not explained by motive, but by the atypical circumstances that generate profitable opportunities.” [[1] In this view, primary commodity exports become significant in our understanding of conflict. Their research has shown that the chances of civil conflict become much higher when a single commodity reached 22% of national GDP. The higher it goes, the greater the chance of conflict. While in modern times, the common commodity that propels civil violence is oil. Another major factor in the onset of civil war is demographic imbalance in a society. A lot of the reason that demographics matter in the drive toward civil conflict, is the economic disparity that is created between the factions. Since resources are not distributed equally across a geographic area, the one faction will always end up controlling the resource in question while the other faction is disadvantaged. This leads us into the next major factor, which is geography. A long with sporadic resource dispersion across a geographic area, geographic isolation provided by mountainous regions and dense forests, create an environment that allows for ease of movement and security for revolutionary groups. Other factors such as the presence of an economic downturn and the stage of economic development a nation or region is in, also factor into the creation and feasibility of a revolutionary movement forming.

The model as presented by Collier and Hoeffler, indicates that when a commodity reaches 32% of GDP a nation has a 22% greater chance of falling into civil conflict. While in modern times commodities that fit this position are oil and minerals, in the 19th century, agricultural products such as cotton or sugar, or commodities like furs would more commonly fit the bill. In the buildup to the American Civil War, cotton would appear to be the prime driver of the conflict. Donald Frasier states that “In 1796, cotton had represented 2.2 percent of US exports. By 1820, this had grown to 32 percent.” [2] This growth seems to correlate with the onset of the nullification crisis and tariff wars that began under the Jackson administration. According to Bruce Levine “By the 1830s, indeed, cotton accounted for more than half the value of all U.S. exports.” [3] This growth would continue and “By the Civil War, the United States produced two-thirds of the world’s cotton.” [4] Raising this percentage to a full 60 percent of the national GDP. With this new understanding, it seems a miracle that the nation did not fall into conflict sooner.

Collier and Hoeffler content in their work that “countries with a highly concentrated population have a very low risk of conflict, whereas those with highly dispersed population have a very high risk.”[5] They go on to contend that “Countries with a highly concentrated population are very safe from conflict while counties which are characterized by a homogenously dispersed population have a high risk of civil war (about 60 percent).”[6] In 19th century America, the majority of the nation was homogenously dispersed with only a small percentage of the populations residing in highly concentrated urban areas. This dispersion was also much greater in the American South and Midwest.

Geography is a crucial factor in determining a nations probability of falling into conflict. Mountainous areas and dense forests provide a security and freedom of movement to revolutionary groups, while also creating geographic chokepoints in shipping lanes that provide opportunities for revolutionary groups to attack trade. Geographic chokepoints that hindered trade existed all across the American South. Since most of the national trade from this time traversed the nation down long navigable rivers, port cities along the southern coasts provided an easy target for the Union whose sole goal would be to predate cotton shipments before they made it to the global market. While this worked against the South, the dense forests and mountainous border regions of the South allowed them the security and freedom of movement to build a force that could resist. Due the geographic issues faced by both nations, the war between the factions turned into a hybrid competition between a land power and a sea power. There are also other geographic issues to consider such as the viability of agricultural production on a large scale. In the case of the United States, it is clear that the American South held the distinct advantage.

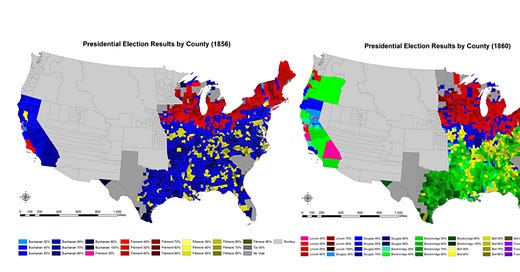

According to Collier and Hoeffler, advanced nations rarely have civil wars. Underdeveloped or unevenly developed nations, however, appear to fall into conflict at alarming rates. The prime reason for this appears to revolve around the heightened sense of fear felt by the people who live in the underdeveloped portions of a nation. Largely this fear is based on the idea that this portion of the nation will be structurally excluded from society as a whole, which fosters a lure of imagined wealth that works to propel one portion of a society into violence against the other. In the years leading up to the American Civil War, a massive anxiety existed in both parts of the nation due to fear that they would be structurally isolated from the nation. To worsen this anxiety the economic downturn known as The Panic of 1857, made many of these fears manifest. The Panic of 1857 was the twelfth recession that the United States had faced since 1800 and affected a much larger portion of the nation that previous recessions. The regions most affected by this recession were New England and the Great Lakes. While business activity in the nation fell almost 20 percent, in New England and the Great Lakes region, economic activity fell by over 50 percent. This economic downturn thrust those regions into despair which caused a shift in voting patterns never before seen in the United States. This shift, aided in bringing the Republican Party from the fringes of American politics into the mainstream. Comparing voting maps from 1856 and 1860, the growth in GOP districts is easily seen.

When the findings of Collier and Hoeffler’s research are overlaid on top of the historical record, the causation of the American Civil War easily shifts from one based on ideological differences and grievance, to one based on the predation of resources and control of the national economy. While ideological differences would have definitely affected the formation of the war and the direction that it went, those factors do not appear to have been sufficient to cause the conflict and would have instead been used to justify violent action. One can assume that it is much harder to obtain and maintain support for your cause if it is solely based on predation and theft. While I have only begun to expand my personal research using Collier and Hoeffler’s findings as a lens, it seems to me that this tool can help us to better understand civil conflicts of the past and prepare for or avert conflicts of the future.

Through the use of this model, it is possible to dispel many myths about the causations of the war. For instance, this research shows that the war was not based on grievances surrounding the institution of slavery, but more on northern desires to capture the excessive wealth of the American South. It would also show that the common states’ rights-based issues are not entirely correct, as the areas that seceded did so in attempts to prevent predation of wealth through tariffs. While this short paper is not long enough to go into depth on all of the conclusions that were made in my master’s thesis, this article should have provided a basic overview. I hope to expand this work into a book at some point and I also plan to post the full thesis on this page so that those interested can dive further into my findings.

[1] Collier, Paul, and Anke Hoeffler. “Greed and Grievance in Civil War.” Oxford Economic Papers 56, no. 4 (2004): 563–95

[2] Donald J Fraser, The Growth and Collapse of One American Nation: The Early Republic 1790-1861. (Roseville, Fraser, and Associates, 2020) Pp. 179.

[3] Bruce Levine, Half Slave and Half Free: The Roots of the Civil War. (New York, Hill, and Wang, 1992) Pp. 21.

[4] David S. Reynolds, Waking Giant: America in the Age of Jackson. (New York, Harper Collins Publishers, 2008) Pp 33

[5]Collier, Paul, Anke Hoeffler, and Nicholas Sambanis. “The Collier-Hoeffler Model of Civil War Onset and The Case Study Project Research Design.” Edited By Paul Collier and Nicholas Sambanis. UNDERSTANDING CIVIL WAR: Evidence and Analysis. World Bank, 2005. Pp. 16.

[6] Collier, Paul, And Anke Hoeffler. “Greed And Grievance in Civil War.” World Bank, 2000. Pp 24.